The zine comes in a A5 white paper, printed in that minimalistic and sober aesthetics that distinguishes the tradition of Dutch design since modernism. Part of the cover folds tight the case of a found musicassette – you can read, under its title Kantoor, the content of the previous recordings: Fred Buscaglione; Famiglia Cristiana: nella casa del padre; We come to dance, and so on. The zine opens with an introduction, called Master/Copy, of the curator Rinus van Alebeek. The last lines remark: “the old never disappears, even if you want to”.

Somehow, this acknowledgement is at the very base of the Kantoor series, and of van Alebeek’s praxis as an artist and curator, if not as lifestyle. He debuted as a writer winning the Geertjan Lubberhuizenprijs with his first novel, De Weg naar Oude God, and throughout the ‘90s he published other books with both the same pseudonym Philip Markus and his real name. His writings, mainly about travelling or walking through space in an ever-receptive mode towards the surroundings passing by, make landscapes and cities speak, trying to find stories in them and in the passage through them. This attention to the environment and the informational potential of its multisensorial elements slowly led him to sound recording: his books Stop the Music and Deep Poland discussed various aspects of the sound experience, but it is since the early 2000s that the writer started to use also environmental recordings on cassettes to narrate stories.

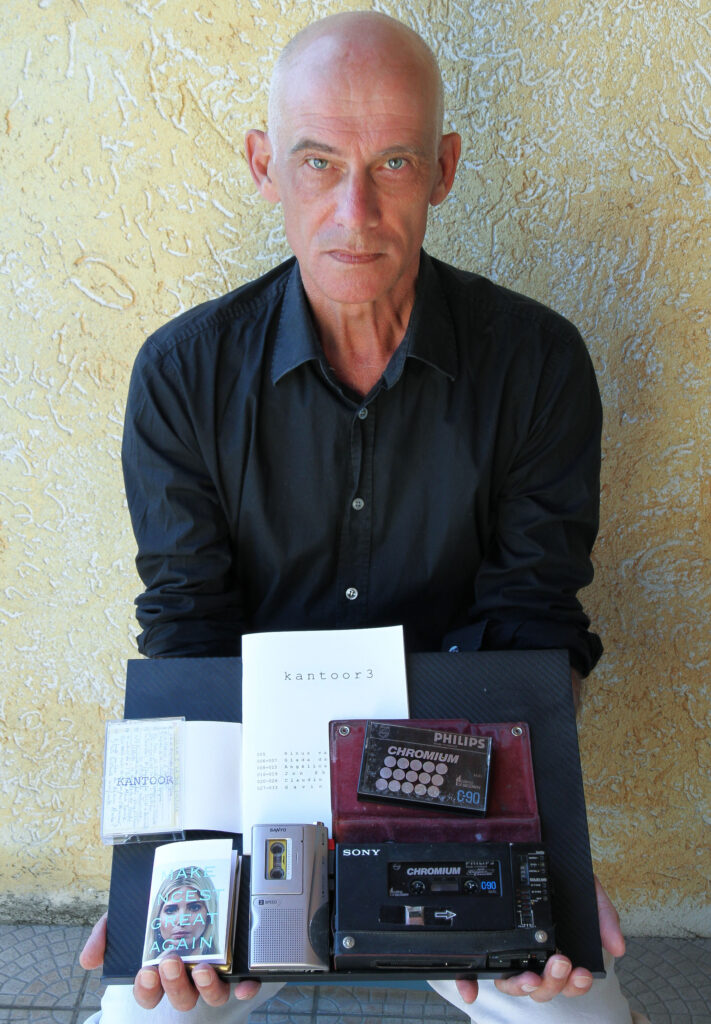

Currently, Rinus van Alebeek is the caretaker of the legendary label Staaltape, co-founder of Radio On Berlin, sound cassette performer and member of several experimental music projects. In his practice, found cassettes are often used as media support or raw material for works and publications, together with field recordings and sound manipulations operated directly with walkmans. This approach encompasses not only a specific sound aesthetic, but also a narrative perspective typical of the novel writer, regarding his tapes also as “a recording of something that happened in the past, or a reference to the passing of time and the layers of experiences that get drowned by our memories.”

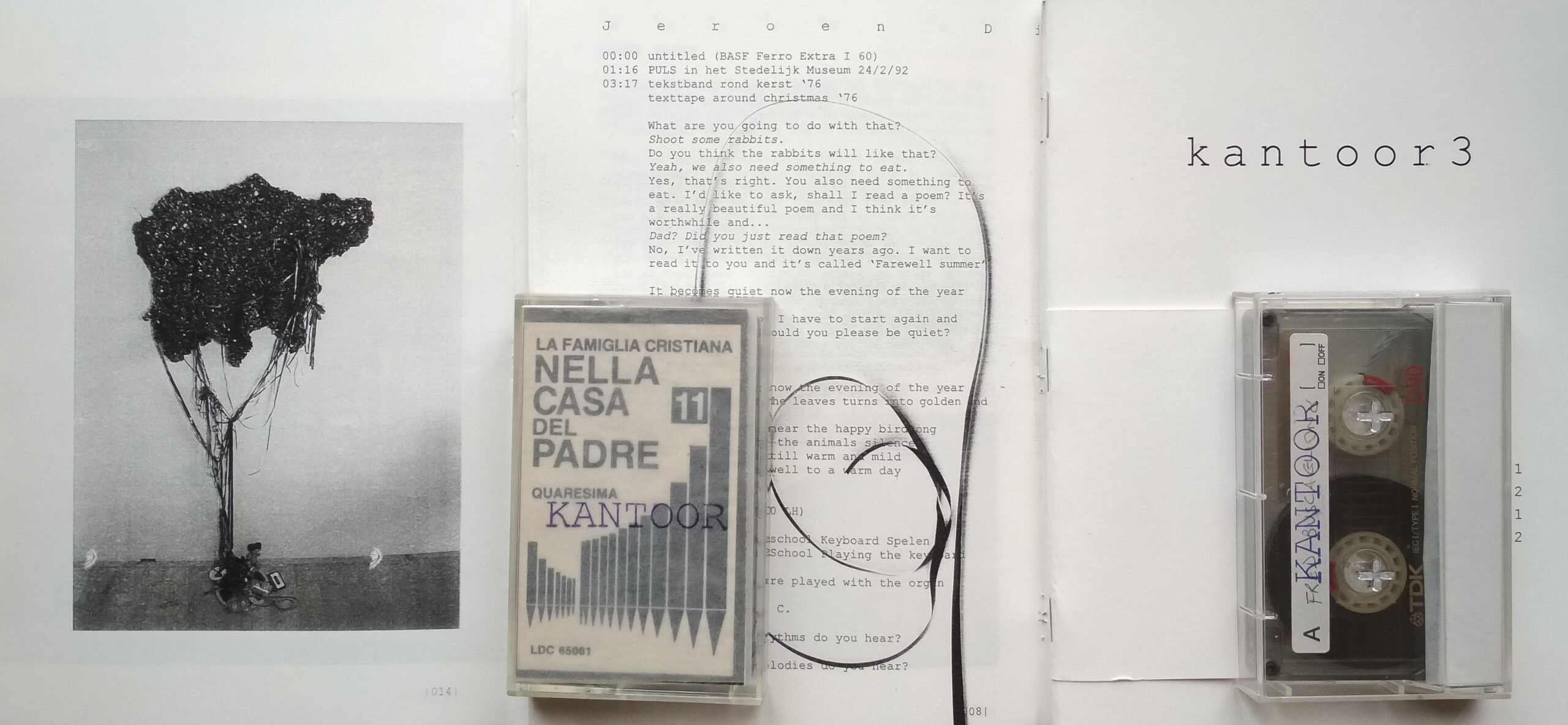

With the project Kantoor, the original movement through various spaces and stories is conceptualized and delegated to others: international artists who incorporate found tapes in their practice in South America, Russia, Europe, U.K. and many other places. Invited to share their fascination for this sound storage medium, they provide the listener, each in their own language, with an insight into their own personal collections and into the horizons of this sound practice niche. Whether found on flea markets, in the trash, in old archives or simply by accident, the recorded material had to be selected according to each artist’s curatorial idea, provided that the pieces were not manipulated nor modified. The recorded material presented in Kantoor goes back as far as the mid 1950s and ranges from family memories to answering machines, religious speeches, astrological séances, poetry declamations and children playing. The international character of such found tapes allows to cut out its own place in time but also in space, mingling Italian chansons with long discussions in Russian, Polish radio pieces, Spanish monologues: the content of these voices is hardly accessible entirely to every listener, giving to each a different understanding of the messages that the cassettes deliver. Rather than covering these semantic gaps with textual interpolations and translations, Kantoor implicitly forces, each in their own cultural and linguistic horizon, to treat unknown words as pure sound, to discover their textures, pauses and intonations, thus creating new resonances with the pieces of actual music that alternate with what we could call “wordscapes” in the tape.

The cassettes, dubbed at home on re-used C90 tapes, come with a Zine released in collaboration with uitgeverij petrichor presenting texts and collages that contextualize the recordings and their history or that expand their content to create other stories. The artists have each contributed in their own way with sound pieces, short essays and stories, simple explanations or lists, pictures and photographs.

The title Kantoor might recall how musicians and poets in Roman and especially Greek antiquity, performing only under inspiration (and possession) of the Muses, could find truth through memory of sound and word patterns. In modern Anglophone contexts, the figure of the cantor is translated into a more Christian or Judaic meaning, indicating the leader of religious singing practices. Funnily enough, the old Dutch term kantoor refers to nothing but the bureau and its inhabitant – a white collar or an archiver, for instance. This ironic duality allows to compare how the conception of artistic processes has changed, together with the role of the author: a contemporary artist –especially if active in the field of sonic sampling and collage, found sounds and field recording– is also a collector, a keeper who, through knowledge and care for the personal archive, is able to reopen, reinvent and rediscover it every time. The projects is an invitation to reflect on archival practices and on exploration of memory, while aiming to explore new ideas and possibilities from fragments of the original story in its immediacy. What was asked were pure segments or fragments in sequence, with or without breaks, without fading nor pitch changes: this archeological character of showcasing various fragments one after the other leads ultimately to sampling various archives throughout the world, thus creating a new archive able not only to give a glimpse of the aural memory created by cassette culture in the span of thirty years, but also able to include the role and personality of the archivers.

The willingly low-key, ironic semantic gravitating around the term kantoor acquires therefore even more meaning, all four releases being a sort of receptacle of words and sounds made of collected and re-assembled patterns. The textual parts are equally important as the sound parts, inviting the artists to explore various forms to find narrative and poetic acts of writing from sound and towards sound. The first series of Kantoor has been closed and almost all of its exemplars are sold out, but a second step of the project is said to be launched, with a twist in the relationship between the author –or the kantoor– and the archive. As the first Zine’s introduction said already, “your life is a tape that gets entangled in the machinery of the cassette player. Get it out, careful. Memories lost. Memories found. Now just start listening”.

Kantoor includes contributions from Rinus van Alebeek, Alan Courtis, Angélica Castello, Ben Roberts, Claudio Fernandez, Ezio Piermattei, Gavin Morrow, Giada Dalla Bontà, Jeroen Diepenmaat, Jon Sheffield, Kristoffer Raasted, Marcin Barski, Mark Vernon, Marta Zapparoli, Michele Mazzani, Roman Voronovsky, Wassily Bosch. You can find more information in Staaltape’s website and bandcamp.

Text: Giada DB.

Gefördert durch die Senatsverwaltung für Kultur und Europa // Sponsored by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe, Berlin